Observed Reality

There’s a small but magnificent ope–nair courtyard hiding in Chattanooga’s Southside, just off of Williams Street. It feels almost sacred, and a little forgotten, like the walls were accidentally built up around it.

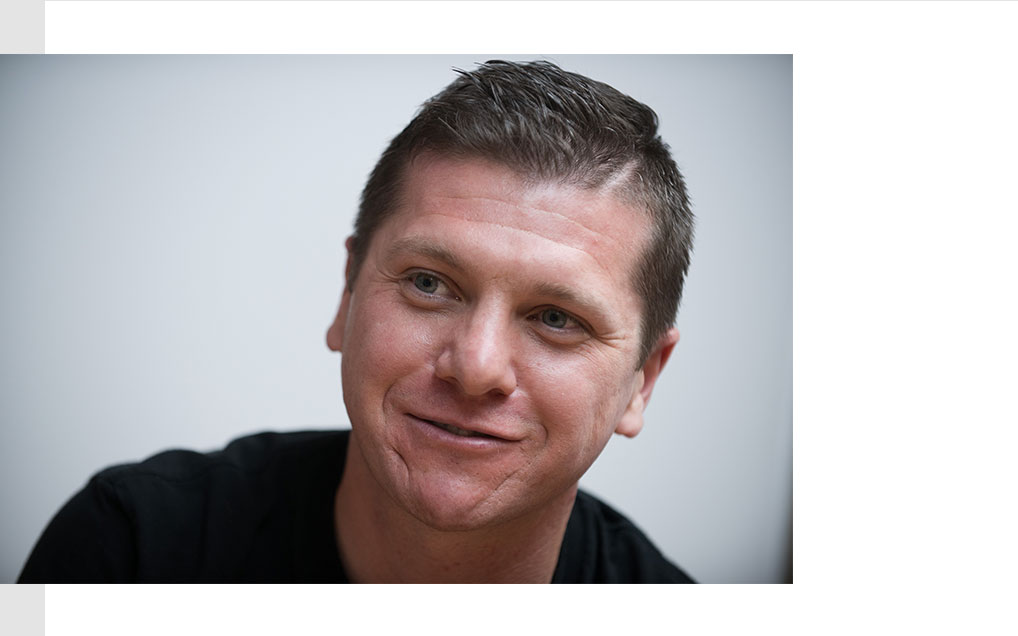

You probably would never know it exists unless you were on your way to artist Timur Akhreiv’s studio. And if you’re lucky enough to visit, you discover that the courtyard is just the crescendo to Timur’s climactic space: the front door opens to a bright white room much longer than it is wide, with sunlight pouring in through a slanted ceiling of skylights.

This is where Timur, a painter, spends his days. He takes a no–nonsense approach to his passion, with a seemingly rigid work schedule that might unhinge a more free–spirited artist. But his studio and his paintings reveal a calm energy.

“I find beauty in everything,”

His accent isn’t distracting, but it’s distinct: he was born in the the South of Russia — Vladikavkaz — where he lived until regional conflict prompted his family’s move to St. Petersburg in 1991. After graduating from the St. Petersburg Iagonson Fine Art School at the age of 18, he immigrated to Chattanooga, where his parents already had settled.

The son of two Russian–trained artists, Timur was influenced strongly, but differently, by the way his father and stepmother approach their own painting.

“My mom, she is not afraid to use colors at all. I learned that from her,” Timur says. “With my dad, it’s attention to details — almost to a degree of obsession. What he does is amazing.”

The Akhrievs’ studio is covered in paintings, and it’s hard to tell whose masterpiece is whose; his parents’ work hangs among his own, and to add to the puzzle, Timur’s pieces vary in medium and style and stroke from one to the next.

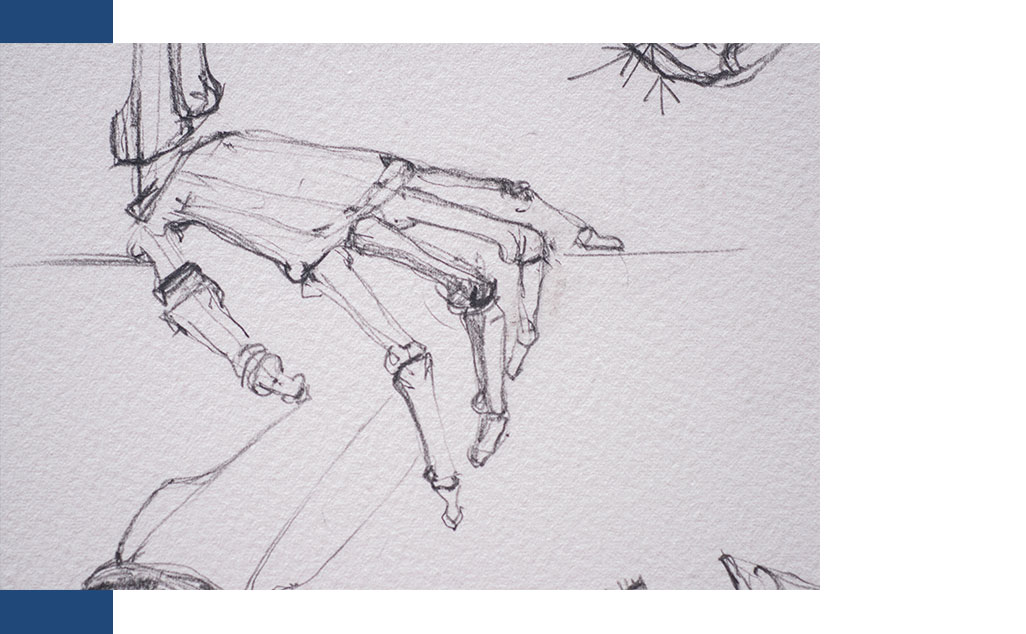

There’s his experimental work, mostly gouache on watercolor paper: tiny pebbles, over and over, in reds and blues and purples; or vertical lines that stretch into infinity. There are less–abstract oil landscapes on linen — blue boats on the water, roped together bow to bow. And there are people: portraits of faces and of bodies in motion.

“I’ve been told that some of my work is topographical abstraction, and I would say my portraiture is contemporary realism,” Timur says. “I’m like my dad, in that I like the details. But I zoom in on the details, versus looking at the whole thing.”

Timur has been formally trained all over the world. After secondary school in Russia, he attended the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in the Fine Arts program. He later moved to Florence, Italy, where he studied at the Florence Academy of Art and Charles Cecil Studios of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture for several years.

“I think that diversity in education is vital,” Timur says. “Russia was great at building a thicker skin. I got maybe three compliments at best the whole time I was there, but they build a strong foundation. UTC is more of a modern approach, and at Cecil, it was a more subtle one.”

Like so many creatives, Timur is his own harshest critic, perhaps a remnant of his Russian schooling. He works into the wee hours of the morning, often still at his easel when the clock strikes three, and rarely lets a painting go unfinished, even if that means it sits in a corner for months and months while he turns his attention to another.

“If I have an image in my head of how I want the painting to look, and it doesn’t look that way, it’s very frustrating to me. I have a really hard time letting go of pieces that I disagree with,” Timur says. “And it can be difficult: it’s not like I wake up inspired. Sometimes, I have to work through not wanting to paint.”

Timur isn’t the kind of artist who seeks out distraction when inspiration is hard to come by. Like Igor Stravinsky, Timur says, he gets his inspiration from his easel. Creative blocks happen, and when they do, he simply stares them down.

But for Timur, place seems to be a kind of muse — wherever his place may be. What Timur sees — “observed reality,” as he calls it — informs his work. Sometimes, it’s coastal Maine, where he’s spent a lot of time over the years on a small island. It’s not one of those with the tourist–filled beaches and charming lighthouses; it’s old and rundown, he says, docks full of lobster harvesters struggling to make a living.

“The thing is, I don’t go there with the romantic idea of Maine. I see the flaws,” Timur says. “It’s beautiful.”

Timur says

While his travels take him far and wide, Timur always comes back to Chattanooga. He’s drawn to Ooltewah, where greenery abounds, or the bridges, where he usually earns a crowd. And sometimes he teaches alongside his father at Townsend Atelier, sharing what he’s learned in his many years as a painter.

But often, he’s in his studio, where his “observed reality” is a simple solitude, and his own education never ceases — because for Timur, that’s what it means to be an artist.

“I follow what Nicolai Fechin once wrote,” Timur says. “If you want to be a professional artist, you always remain a student. And so, I do.”