Hacking

The World

Since the mid-2000s, the "maker movement" has grown from a small community of high-tech tinkerers to a culture in and of itself. Years later, it's still gaining momentum and recognition across the world. Yet in spite of its universality, or maybe because of it, the maker movement has yet to be truly defined. And probably, it never will: definition would only confer constraint, and the maker movement knows no bounds – because, theoretically, anyone can be a maker.

"A maker is someone who has recognized and accepted that the world is not predetermined and predefined. Makers see the world as a place that can be hacked," says Meg Backus, a Chattanooga transplant, librarian by profession and self-described maker.

The maker movement has its roots in engineering and technology. In fact, it's been called a present-day "industrial revolution." But that can be misleading, because it implies creation solely for the sake of efficiency or utility – and that's not what the movement is about.

“We make because it's delightful,” Meg says.

“Whether or not these things serve a purpose isn't the point.”

It's an intersection of antonyms: art and science, humanities and engineering. Technology infused with creativity, or creativity inspired by technology. It's old – in the sense that makers have always existed – but new, in the way that they're coming together and being celebrated.

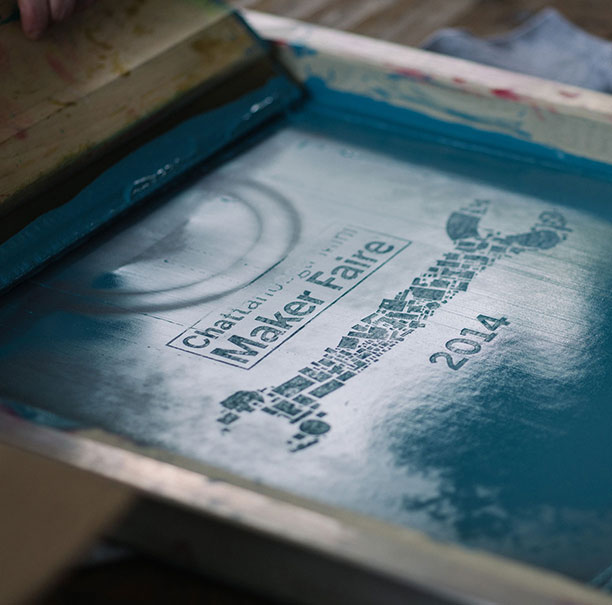

At the heart of this celebration is the Maker Faire. A brand-name festival with West Coast roots, Maker Faire launched in 2006 and has become a means to observe and experience the maker movement. From New York to Tokyo, cities large and small have embraced this unpolished, unconstrained, uncensored event. Maker Faire calls itself as "the greatest show (and tell) on Earth," and if that conjures up images of a circus, then then it's aptly named –because it's odd and unpredictable, in the best possible way.

“The Maker Faire opens up space for people to express what they've got and who they are,” says Meg Backus, who helped organized Chattanooga's Maker Faire. “People are a lot weirder than it's socially acceptable to be. This forum makes it okay to encounter the weirdness.”

Maker Faire made its Chattanooga debut on a drizzly October day, in the form of a Mini Maker Faire: a smaller-scaled event with the same spirit and theme. Held under a large, open-air pavilion on Chattanooga's Southside, it looked less festival, more science fair: simple booths lined the periphery, most of them manned by two or three makers providing explanations and demonstrations to curious onlookers.

One maker, Ezra Reynolds, stood alone, a table of contraptions displayed before him. Small, plastic, brightly colored, uniquely shaped: they looked like toys. And many of them are, indeed, for children. But they're not toys.

Ezra is an engineer at Signal Centers, Inc., a Chattanooga-based nonprofit that provides comprehensive developmental services for people of all ages who struggle with physical disabilities. He specializes in assistive technology: helping clientele find solutions that enable them to live more independently.

“There are a lot of helpful things out there that people with disabilities haven't even imagined,” Ezra says. “I always keep a box of Kleenex in my office because when we find the right piece of technology for someone, it can be completely life-changing.”

Unfortunately, the devices that can change a life can also cost a fortune. As a nonprofit, Signal Centers has limited resources, and most of its clients have their own budget restrictions. Beyond financial concerns, sometimes what's needed doesn't even exist in the market.

And that is when Ezra the engineer becomes Ezra the maker, pulling together creative energy and technical dexterity to produce something wholly new: if the right tool isn't affordable, or doesn't exist, Ezra crafts it in his head. Then he builds it, either by hand or by computer and machine, often with a 3-D printer. A weaving loom for people in wheelchairs; a contraption that opens a microwave without requiring a finger;

an adapted phone that removes limitations when dexterity is limited. It's imaginative, inspired resourcefulness, and it's exactly what drives the maker movement.

“In my own personality, there are two different, dominant traits: the artist, and the engineer,” Ezra says.

“The artistic side is less restrained, the engineer side is more so. Through my work, I've found a way to balance both sides of myself.”

Aesthetically, his creations don't scream high-tech; they aren't shiny or sleek. They're beautiful, though, because of the spirit in which they were made, the opportunity that they represent, and the meaning they hold for the people who use them.

“Ezra is the purest

example of a maker,”

Meg says.

Meg says. “He's using technology to solve problems, in a creative, tangible way. He could just as easily show his work in a gallery as he could give it to the people he serves. It's art.”

Ezra represents a growing number of Chattanoogans who identify with the maker movement. The organizers of Chattanooga's Maker Faire were hoping to have at least a dozen makers participate; they ended up with more than 50, and almost 3,000 people attended the event.

“We had a tremendous showing in our first year. I don't know what explains that, other than it's just the Chattanooga way,” Meg says. “When something like this comes along in other mid-size cities, there's often a shared skepticism. People think, this will never work. But in Chattanooga, the response is always: let's give it a try.”

Meg says. “He's using technology to solve problems, in a creative, tangible way. He could just as easily show his work in a gallery as he could give it to the people he serves. It's art.”

Ezra represents a growing number of Chattanoogans who identify with the maker movement. The organizers of Chattanooga's Maker Faire were hoping to have at least a dozen makers participate; they ended up with more than 50, and almost 3,000 people attended the event.

“We had a tremendous showing in our first year. I don't know what explains that, other than it's just the Chattanooga way,” Meg says. “When something like this comes along in other mid-size cities, there's often a shared skepticism. People think, this will never work. But in Chattanooga, the response is always: let's give it a try.”